Potato peelers, sock knitters and moss collectors

Remarkable volunteers from the First World War

Last updated 10 June 2022

As fathers, brothers and sons set off to the front, what happened to those left behind?

90,000 people volunteered for the British Red Cross during the First World War.

Thousands of our brave sailors and soldiers are standing ready to defend Britain’s shores and uphold her honour. Their sufferings will be great and it is to us that they will look for comfort and relief. That comfort must not be denied them.Queen Alexandra, president of the British Red Cross Society in 1914

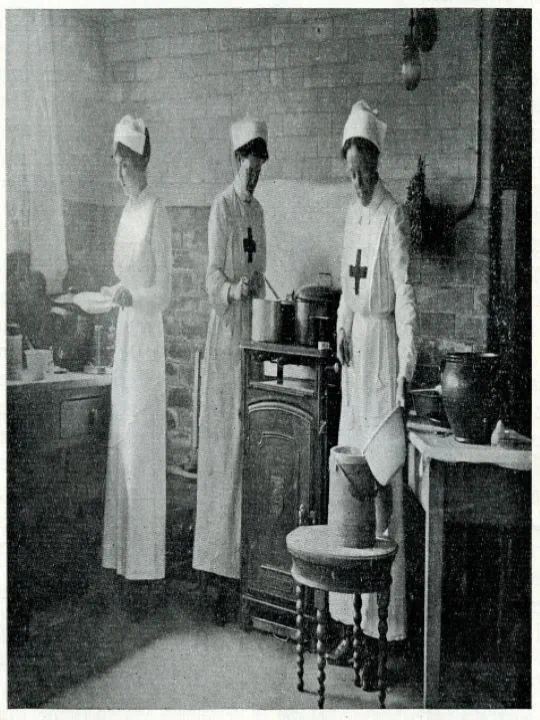

Many of these volunteers, known as ‘VADs’ (voluntary aided detachments), were nurses, stretcher bearers and ambulance drivers. Some risked their lives helping injured soldiers at the front. Others saved lives at home, nursing sick and wounded servicemen in UK hospitals. Red Cross nurses bandaged wounds, changed dressings, and washed bed sheets. They filled hot water bottles, provided clean pyjamas and offered nourishing meals.

But this is not the story of those fantastic nurses. This is the story of those behind the scenes. The people who made the meals, the bandages and the hot-water-bottle covers.

The sock knitters. The potato peelers. The women who sewed pyjamas.

What’s your idea of treasure? Gold, pearls, antiques – or soap?

For weary refugees and prisoners of war, treasure was a bar of soap and a handkerchief.

Volunteer Ann Curtis, from Suffolk, knew a lot about this kind of treasure. She put in 88 hours of needlework to create individual treasure bags.

“About 1200 officers and men arriving in Switzerland for internment from Germany were provided with chintz treasure bags containing washing materials, handkerchiefs etc, which were very popular,” reported the Red Cross.

“Indeed, many of the bags were recognised three months later at the general repatriation doing duty as hand luggage.

"About 3,000 of these fitted bags were handed to the prisoners passing through Switzerland on their way home from Germany after the Armistice.

“Another 550 were given to civilian refugees passing through from Austria, Poland, Hungary, etc and were quite invaluable to the women, many of whom were accompanied by small children.”

The organisation relied on hundreds of volunteers like Ann to stitch, sew and knit products for prisoners of war and hospital and wards.

The Red Cross issued material and standard patterns to follow. Hour after hour, knitting needles clicked and scissors snipped in communities across the UK.

When she wasn’t sewing treasure bags, Ann Curtis made hot water bottle covers.

Eighty-three-year-old volunteer Martha Antobus in Cheshire knitted 40 pairs of woolly socks.

And Mr Stevenette, described as "an old gentleman of over 80, knitted 44 mufflers – his knitting exceeded all other workers.”

There was such huge demand for these items that in 1915 the Red Cross set up the Central Work Rooms. Throughout the war over 1,200 women worked in these London offices. They produced 705,500 bandages and 75,530 garments ranging from hot water bottle covers, pyjamas, dressing gowns and kitbags to pants, surgeon’s gowns, socks and pillow cases.

They used flannel, sheep’s wool and even some dog’s wool made from long-haired breeds such as Pekinese and Pomeranians.

Sewing all these garments was not without its perils. VAD nurse Helen Beale wrote to her family:

"We are very pleased this evening as the pin that the girl swallowed on Wednesday last has just emerged safely – she has been having cotton wool sandwiches and suet pudding etc. It really is rather wonderful to think that it has travelled so far inside her without pricking!"

Sometimes ‘doing your bit’ meant getting your feet wet.

During both world wars you could find children and adults doing their bit by getting muddy and wet in peat bogs. They were collecting sphagnum moss, a small, bright green plant that was often called ‘bog moss’. It was a time-consuming, cold and uncomfortable job.

The moss was harvested and dried on an industrial scale, particularly during the First World War. In those days, before antibiotics, this moss was mildly antiseptic and could soak up a lot of fluid.

In short, it was a brilliant wound dressing.

In Ireland, Red Cross sphagnum moss centres were set up in every county. Women volunteers collected enough sphagnum moss to make close to one million dressings.

Ethel Adams was one of these women. Volunteering in County Tyrone, Ethel gathered sphagnum moss almost full time. She picked, gathered and dried the moss, sending it off to the Red Cross depots in Belfast and Armagh. She paid for the postage herself as another way to support the cause.

“In County Tyrone, sphagnum moss depots did continuous work from 1916 to October 1918,” recorded the Red Cross journal.

“Sending their supplies to Derry and Belfast, they were manufactured into dressings, the moss from this county having been considered of exceptionally good quality.”

Ethel did not just collect moss on her own – she organised a local group to gather as much as possible.

As if that wasn’t enough, she then volunteered at the Belfast moss depot. Here she clocked up 100 hours of volunteering in just three months. Ethel received a war workers badge in recognition of her efforts.

If you think hospital food is bad today, spare a thought for patients during the First World War.

Hospital caterers had a budget of just 20 pence per day to cook up a varied diet for one patient. Anything more expensive was considered an extravagance.

Then food shortages began in 1917. By this time the Red Cross was running temporary hospitals across the UK. Known as auxiliary hospitals, they treated injured servicemen – but they also had to feed them. We worked with the Ministry of Food and the War Office to ensure our patients had enough to eat.

Anne Auden was a Girl Guide who volunteered in the kitchens of Brookdale Red Cross hospital at Alderley Edge, Cheshire. For more than two years she popped in every week to roll up her sleeves and peel hundreds of potatoes.

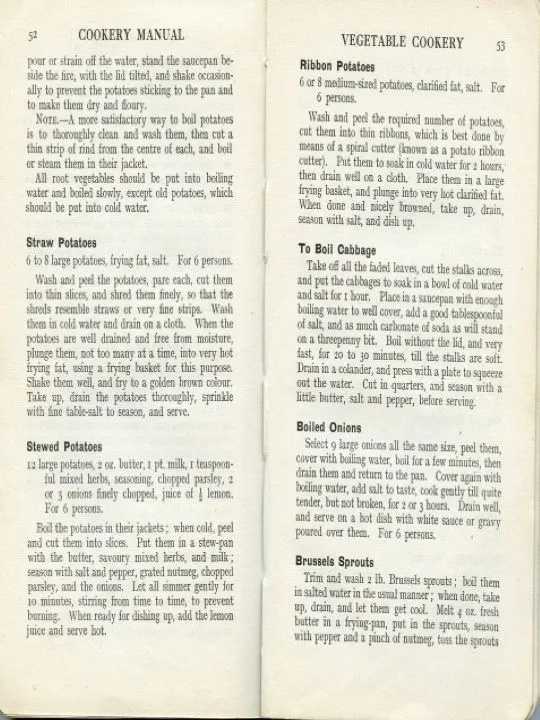

The Red Cross produced a cookery manual suggesting different ways to cook potatoes for patients (boil, stew, bake and fry in ‘ribbons or ‘straws’).

Many favourite foods – sugar, tea, meat, margarine, butter, cheese, fish, suet, golden syrup and jam – were all in limited supply. Bacon was off the menu as it was sold at double its pre-war price.

Breakfast in a Red Cross hospital was, therefore, porridge, cold boiled ham or fishcakes.

Dinner might be stewed tripe, boiled mutton, tapioca and savoury hash – no doubt made from some of Anne’s peeled potatoes.

For afters there were baked jam rolls, rhubarb and custard or bread and butter pudding. But some cooks struggled to get the recipes quite right...

One woman volunteered at a Red Cross hospital as a kitchen maid. In the topsy turvy world of the war, old class divides were often blurred. Women from rich families volunteered alongside working class women and girls.

This particular woman found herself serving as a kitchen maid to her own cook. But she did not share her cook’s expertise.

The Red Cross journal from 1916 reports that this woman “had been in trouble several times for her incompetence, and was passing a sleepless night of worry in connection with a lemon sponge." It had not come right, and she knew what awaited her in the morning.

“Suddenly she had an idea. Rising from her bed, she crept to the kitchen… What exactly she did will never be known, but a message of thanks came down from the ward next day, with the comment that it was the best bread-and-butter pudding the patients had ever tasted.”

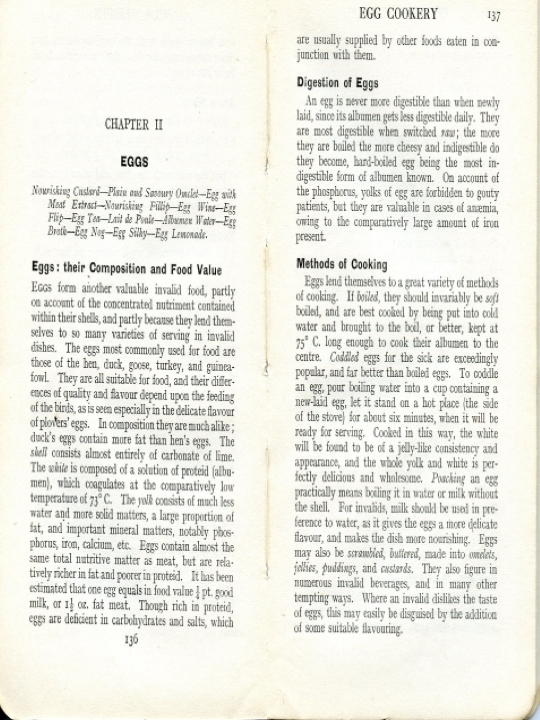

Clickety-click. Clickety-click. Clickety-click. In the circle of light a VAD is frothing the white of an egg. Behind, in the ward, men badly gassed are panting away their lives. Over all, the moon shines.

This diary extract was written by a nurse in 1918. It would have been familiar scene in hospital wards across Europe.

Frothed egg whites were fed to acutely ill patients, many of whom couldn’t eat solids after facial injuries. A standard meal was ‘egg flip’ – raw eggs, which could be mixed with caster sugar and sherry or brandy.

Cooked eggs were a good source of iron and protein for men on the mend. Red Cross VAD nurse Janet Garrod wrote that all her patients got “great amusement (from) Kelly of the Dublin Fusiliers who thinks nothing of eating five hens’ eggs for his breakfast every morning. True he needs it after weeks of starvation through a hole in his jaw.”

'National egg collections' were organised across the UK to supply hospitals. Egg collecting was a huge task for the Red Cross. In Shropshire alone, Red Cross volunteers collected between 53,000 and 71,000 eggs every year throughout the war.

In Derbyshire, volunteer Nina Louise Anther picked her way through feathers and chicken poo for three years. Nina collected an astonishing 5,000 eggs for the Red Cross hospital in Hathersage between 1914 and 1917. We can only imagine how much time she spent braving the elements and the hens – her record card states her hours were “impossible to count.”

Like many volunteers, Nina sent her eggs to her local hospital. But there was also a national demand for this nutritious food.

The Red Cross created a 'national egg collection department' in Belfast. From here, donated eggs were sent off to hospitals in Ireland, England, Scotland and Europe. This precious cargo was transported across Ireland in the backs of ambulances. The department received £20,500-worth of eggs.

How did an army of 10,000 volunteers turn this...

...into this?

When war broke out, Queen Alexandra made a public appeal.

“As president of the British Red Cross Society I appeal for your help… Much money will be needed and many gifts if we are to faithfully discharge our trust and be able to say when all is over that we have done all we could do for the comfort and relief of our sick and wounded. The heart of the great British nation will surely and generously go out to those who are so gallantly upholding the cause of their country.”

And boy, did the British nation respond.

They offered their time, money, homes and even their yachts to help the cause. Red Cross fundraisers hit the streets for a national day of fundraising on 21 October 1915.

“Gentle ladies by the thousand” sold flags in London according to The Telegraph. Some were on duty and ready to fundraise by half past three in the morning. “The number of dames on duty during the day” would reach 10,000.

But volunteers weren’t just out in the capital.

“In the country all kinds of schemes were devised for raising money” wrote fundraiser-in-chief Miss May Beeman. “In one place two pigs were sold by mock auction; the pigs changed ownership several times.

Perhaps the most novel was a marrow-seed competition. So enthusiastically was this taken up that there were 1,580 entries raising £35 17s 11d [over £1,700 today]. Contestants had to guess the number of seeds in a vegetable marrow.”

By 1918, the Red Cross needed funds more than ever. As the mayor of London put it, the Red Cross was frantically “relieving the suffering and ministering to the needs of the men who are fighting in our battles.

“The cost is nearly £100,000 per week or nearly £10 per minute.”

Volunteer Annie Harrison came up with a unique fundraising idea. Annie, from Surrey, volunteered in the canteen at Horton hospital. She also spent time on the wards, chatting to patients and entertaining them with whist drives.

She saw that the patients needed more than the hospital could provide. So she set about on a fundraising mission.

Annie collected 6,000 farthings. She silvered them all and engraved each one herself with the word ‘Horton’. Then she sold the farthings to supporters, raising £28 – the equivalent of around £1,200 today.

The hospital used the money to buy “invalid chairs for the wards and invalid comforts.

More stories from World War 1

The heroic women of WW1: a nurse's diary

Peggy Arnold was a WW1 nurse serving on the frontline. Here we celebrate her bravery, and the bravery of volunteers like her.

Remembering Edith Cavell: a brave British Red Cross nurse

We remember brave nurse Edith Cavell who was killed in 1915. Her crime? Moving Allied forces to safety.

Marie Curie: invisible light, the Red Cross and WWI

Curie achieved so much in her lifetime, from transforming the face of medicine to service on a WWI battlefield as a Red Cross nurse.

Help us reach people in crisis

We have been supporting and comforting those in need around the world for over 150 years. If this story has inspired you, click below to support our work and learn more about how you can help us help others.

Donate